In a few temples in Yamagata Prefecture, the preserved bodies of monks known as Sokushinbutsu can still be seen today.

They are the remains of ascetic monks who, hundreds of years ago, entered a final state of meditation while still alive and calmly accepted death.

As a result, their bodies remained in a naturally preserved condition.

Most people have the same questions when they first hear this.

“Why would anyone choose such a path?”

“How is it even possible for a body to remain like that?”

“And why are so many of them in Yamagata?”

Sokushinbutsu are not simply mummies or strange curiosities.

They represent the strong will of monks who devoted their entire lives to spiritual training and sought to continue praying for the people even after death, shaped by the social conditions of their time.

In this article, we will look at what Sokushinbutsu are, why monks chose this path, how they were created, why so many are found in Yamagata, and where you can actually see them today — all from the perspective of a traveler.

What Are Sokushinbutsu?

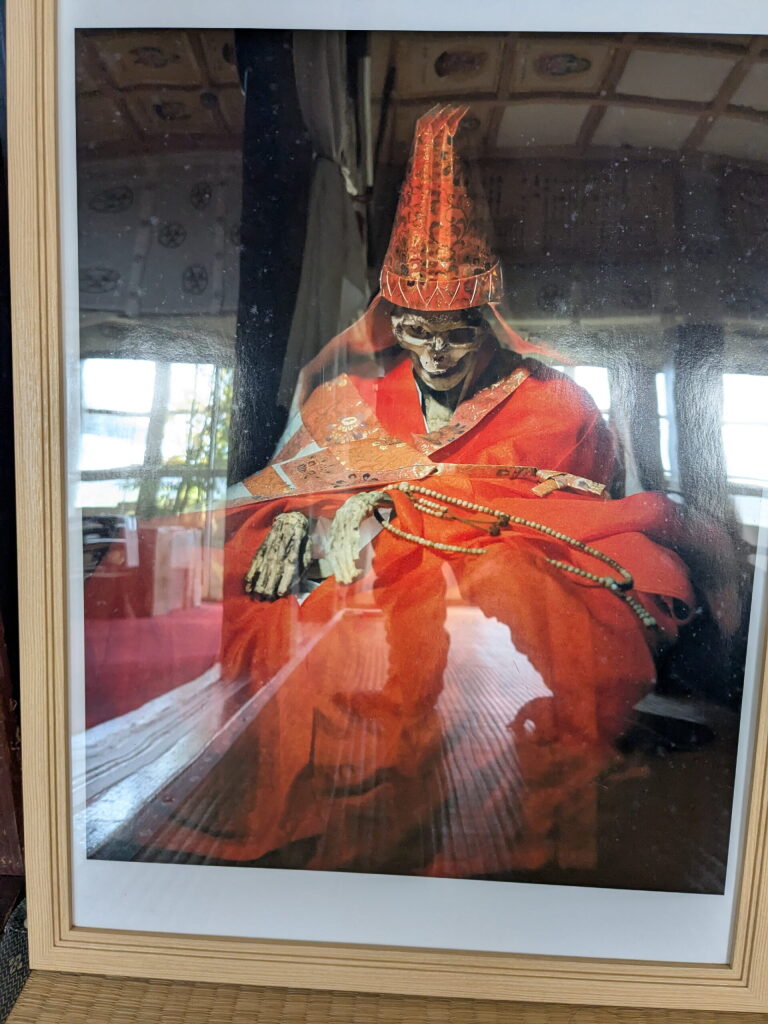

Sokushinbutsu refers to monks who, after many years of extreme ascetic training, entered an underground stone chamber while still alive and calmly accepted death through prayer.

Their bodies remained in a naturally preserved condition and are now enshrined in temples, where they can still be viewed today.

The important point is that Sokushinbutsu were not created through a technique to preserve a corpse.

The goal was spiritual: to reach a state close to Buddhahood through ascetic practice and to continue praying for the people even after death.

That is why what remains is not a statue or a relic, but the monk’s actual body.

Cultures that preserve human remains exist in many parts of the world.

However, Sokushinbutsu in Japan — especially those found around Yamagata Prefecture — are unique because they were part of a religious practice and are still enshrined and openly displayed in temples today.

In particular, many Sokushinbutsu are concentrated around the Dewa Sanzan area (Mount Haguro, Mount Gassan, and Mount Yudono).

Why Did Monks Choose to Become Sokushinbutsu?

This is probably the part that feels most difficult to understand.

“Why would anyone deliberately choose such a path?”

Sokushinbutsu were not about leaving a preserved body behind.

For the monks, the final act of entering meditation while still alive was a way to continue praying for the people even after death.

In other words, it was not about ending one’s life, but about extending one’s spiritual role beyond death.

At the time, life in northeastern Japan was extremely harsh.

Famines, epidemics, and natural disasters occurred repeatedly.

People lived with constant uncertainty about what tomorrow might bring.

In such conditions, communities needed something they could rely on spiritually.

Highly trained monks were seen as figures of last resort — something like a spiritual anchor for the region.

In mountain worship traditions such as those around Dewa Sanzan, ascetic training itself had special meaning.

Mountains were places cut off from ordinary life, and monks were respected as people who stood at the boundary between the human world and the spiritual world.

This made it easier for the idea to take root that a monk could continue protecting the community even after death.

Of course, it would be wrong to assume that all monks had the same motivations.

But if we see Sokushinbutsu not as “strange mummies,” but as an expression of a deep desire to leave behind a lasting prayer, the practice becomes much easier to understand.

How Did Sokushinbutsu Come Into Existence?

Most people naturally ask:

“How could something like this even be possible?”

Sokushinbutsu were not created simply by entering an underground chamber at the end.

They were the result of many years of ascetic training that gradually transformed the body.

A commonly described general process looks like this.

First came extremely strict dietary restrictions.

This was not simple fasting.

Monks gave up grains such as rice and wheat and shifted to a life sustained mainly by nuts, seeds, and wild plants gathered in the mountains.

As the stages progressed, their diet was said to move closer and closer to “wood” — including tree bark, roots, and pine needles.

The goal was to reduce body fat and moisture as much as possible and to make the body less prone to decay.

After continuing such practices for years, the monk would enter the final stage:

he would go into an underground stone chamber while still alive and continue praying until death.

This stage is known as nyūjō.

Even with the same practices, only a very small number of monks actually became Sokushinbutsu.

It was never something anyone could achieve just by trying.

That is why only a limited number of Sokushinbutsu remain today, and why they are concentrated in certain parts of Yamagata.

Why Yamagata? The Numbers and the Reasons

Around 18 Sokushinbutsu are believed to exist in Japan today.

Of these, eight are found in Yamagata Prefecture.

In other words, nearly half of all known Sokushinbutsu are concentrated in one region.

(Some sources list 17 instead of 18, and the exact count varies slightly depending on how they are classified.)

So why Yamagata?

This is not a coincidence.

Several conditions came together.

First is the strong tradition of mountain worship centered on Dewa Sanzan (Mount Haguro, Mount Gassan, and Mount Yudono).

In this region, ascetic training itself carried special significance, and monks who undertook extreme practices were deeply respected.

Sokushinbutsu were seen as the final stage of such mountain asceticism.

Second is the support of the local communities.

A monk could not become Sokushinbutsu alone.

People had to watch over the final meditation, exhume the body later, enshrine it, and continue to care for it.

Around Dewa Sanzan, there was a cultural atmosphere that accepted such practices as something that could happen.

Third are the natural conditions.

Yamagata’s inland and mountainous areas are cold in winter and relatively dry.

This made it more likely for bodies to remain preserved rather than decay.

As these factors combined, the belief that Sokushinbutsu could exist in this region grew stronger, and the practice continued in a chain of faith.

That is why Yamagata is the most reliable place in Japan to see Sokushinbutsu today.

Sokushinbutsu at Dainichibō (Taki-Sui-ji Temple)

Yamagata is home to eight Sokushinbutsu, but many of the temples require advance reservations.

One of the most accessible places where you can see a Sokushinbutsu without a reservation is Dainichibō, part of Yudonosan Sōhonzan Taki-Sui-ji.

The Sokushinbutsu of Monk Shinnyokai is enshrined here and can be viewed by the public.

For first-time visitors, this is one of the easiest places to see a Sokushinbutsu in person.

Address:

11 Nyūdō, Ōami, Tsuruoka, Yamagata View on Google Maps

How to Get There

By Bus

Dainichibō can be reached by bus from Tsuruoka Station.

You will need to transfer once, so it is best to leave with plenty of time.

For details on how to reach Tsuruoka Station, please refer to our separate article.

1) Tsuruoka Station → Asahi Chōsha Bus Stop

Take a bus from platform 2 at Tsuruoka Station and get off at Asahi Chōsha Bus Stop.

Travel time: about 37 minutes

Fare: 870 yen

2) Asahi Chōsha-mae Bus Stop → Ōami Kyoku-mae Bus Stop

About a one-minute walk from Asahi Chōsha Bus Stop is Asahi Chōsha-mae Bus Stop.

Transfer here and get off at Ōami Kyoku-mae Bus Stop.

Travel time: about 21 minutes

Fare: 200 yen

3) Ōami Kyoku-mae Bus Stop → Dainichibō

From Ōami Kyoku-mae Bus Stop, it is about a 10-minute walk to Dainichibō.

Important Notes for Bus Users

Bus services on this route are very limited.

The earliest bus from Tsuruoka Station departs at 9:03 a.m., and it is safest to plan your trip around this service.

Be sure to check the return bus schedule as soon as you arrive.

The next bus may be a long time away.

By Car or Rental Car

If you are already traveling in the Yudonosan area by car, you can continue directly to Dainichibō.

Travel time:

About 30 minutes from the Yudonosan area

About 40 minutes from central Tsuruoka (as a rough guide)

Compared to public transportation, traveling by car is much easier.

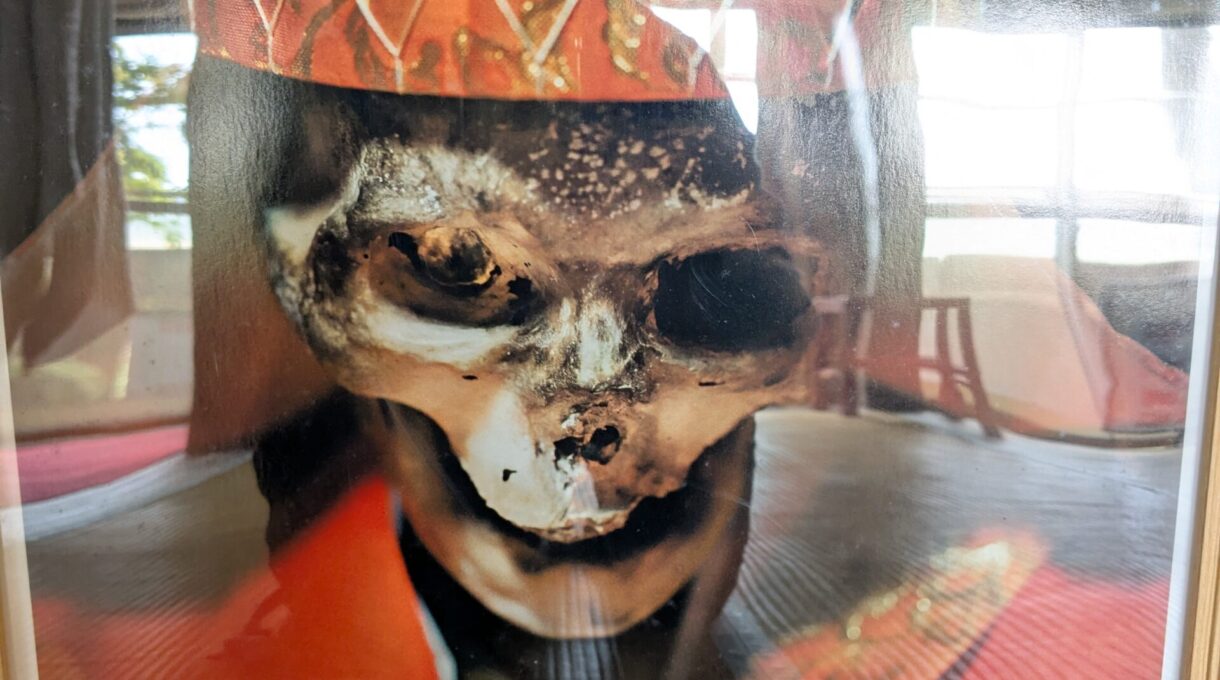

Inside Dainichibō

The temple grounds are small and consist mainly of a single main hall.

The entrance is on the front side of the building.

The admission fee is 800 yen, which you pay at the entrance.

Photography of the Sokushinbutsu itself is not allowed.

However, you may photograph the explanatory panels and related images inside.

Visiting Hours:

April–November: 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (last entry 4:30 p.m.)

December–March: 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. (last entry 3:30 p.m.)

Admission Fee:

Adults: 800 yen

Junior & senior high school students: 600 yen

Elementary school students: 500 yen

Other Sokushinbutsu You Can Visit in Yamagata

Kaikō-ji Temple (two Sokushinbutsu)

Address: 2-7-12 Hiyoshi-chō, Sakata, Yamagata View on Google Maps

Reservation: Not required (closed on certain days)

Visiting hours:

April–October: 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.

November–March: 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m.

Admission fee:

Adults: 500 yen

High school students: 300 yen

Elementary & junior high school students: 200 yen

Chūren-ji Temple

Address: 92-1 Nakadai, Ōami, Tsuruoka, Yamagata View on Google Maps

Reservation: Required (irregular holidays)

Visiting hours: 10:00 a.m.–2:00 p.m.

Admission fee:

Adults: 800 yen

Students: 500 yen

Nangaku-ji Temple

Address: 3-6 Sunadamachi, Tsuruoka, Yamagata View on Google Maps

Reservation: Not required (closed on certain days)

Visiting hours: 8:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m.

Admission fee:

Adults: 400 yen

Children: 300 yen

Hōmyō-ji Temple

Address: Uchino 388, Higashi-Iwamoto, Tsuruoka, Yamagata View on Google Maps

Reservation: Recommended

Visiting hours: 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m.

Admission fee: 500 yen (free for high school students and younger)

Kōkō-in Temple (Shirataka Town)

Address: 544-1 Kurokamo, Shirataka, Yamagata View on Google Maps

Reservation: Required (may not be available during funerals or memorial services)

Visiting hours: By appointment

Admission fee: Please inquire (not clearly listed on official sources)

Note:

All information in this article is based on conditions as of November 2, 2025.

Hours, fees, and reservation requirements may change. Please check directly with each temple before visiting.